The work I have undertaken during the Major Study project has been concerned with holding space and place.

During my research into three major works for my dissertation I chose the works Metronomic Irregularity II (1966) by Eva Hesse, Friendship(1965) by Agnes Martin and Gold Field Paired for Ross and Felix(1995) by Roni Horn. I was looking generally at the shift in any given artists’ career and after a discussion during a tutorial with visiting lecturer Joanna Hyslop in July 2020, I really began to be fascinated about these transitional spaces within artworks and the artist’s drive to change their work.

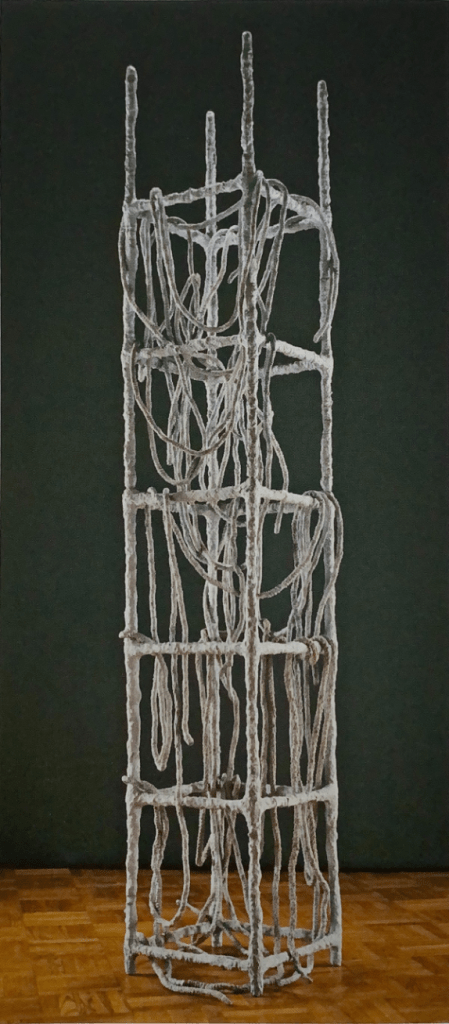

My research into this transition I identified for Eva Hesse’s work started in the year of 1965 when she spent a year working in Germany with her husband Tom Doyle. She began to use materials from the factory they shared as a studio and made three dimensional wall based works with them. The change from painting to three dimensions began in Germany but when she returned to New York, she began again with a table rasa. The work lost the vibrant colour. She made her first free standing sculpture in 1966, Laocoon standing ten feet high ladder like with cords wrapped around in loose curves. Her want was for ‘irrational’ element that was not powerful enough to conquer or balance the rational element. In Lippards mind the piece had less pathos and personnage once Hesse made the piece into a “better sculpture”. (Lippard, 1976)

Hesse worked in series and she made the Metronomic Irregularity series in response to a call from Lippard. It is a work that was transitional for Hesse and technically very challenging. It was born out of a desire to change her work for the show she had been asked to be in by Lippard Eccentric Abstraction. Hesse had visited the venue and the ceiling was too busy for the piece Laocoon so she decided to make new work. Thee were described by Lippard as ‘Hesse’s last “paintings”‘(Lippard, 1977 pp79) so this was clearly her final transition from painting to sculpture that she became so prolific and well known for. What I found so intense about this particular piece was that it started life as a vertical piece. This isn’t very well known and I had to really dig deep into Lippard’s text to unravel this. I also searched Hesse’s diaries to try to find out if she had written about this piece. Lippard mentions that Hesse had made notes and drawings of Metronomic Irregularity being vertical. I searched the Oberlin archives too. I could not find anything to back up this anecdotal evidence. Lippard shows pen and ink notebook pages from Hesse’s notebooks on page 82 of her catalogue raisonee but these notes were made a year or two after Metronomic Irregularity series had been made. It is possible that during discussions that Hesse made notes and drawings to show Lippard. Lippard had thought the new work a little too slick, not quite what she had imagined “at the time, I was somewhat surprised at the precision of Metronomic Irregularity II, although that same precision amounted to the fact to the maze-like obsessiveness (image merged with process) I found one of the most attractive aspects of Hesse’s work.” Lippard went on to say that she had conceived this exhibition to show her more organic work such as Several (1965) and Ingeminate (1965) but thought these were completely overshadowed by Hesse’s huge undertaking in Metronomic Irregularity II.

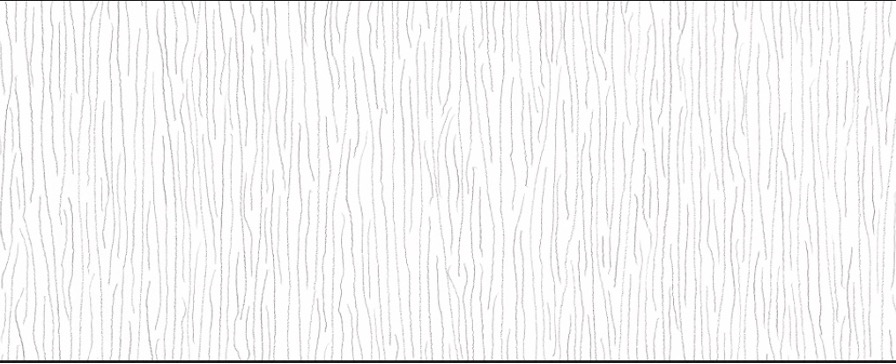

What I find really fascinating within Hesse’s ouvre is that she did not stick rigidly to a type of work, and even with some success did not rest in a place of complacency. She had an obsessive nature and worked with the materials she found in series and with repetition. She took her subject and pushed it until it broke. From this point onwards her work is serious and she works with people who can help her make the work, even if sometimes she physically cannot realise it. With Metronomic Irregularity II it did in fact break off the wall. Sol LeWitt had not fixed it well enough and she had to remake the piece in situ. It was an event LeWitt never forgot. My dissertation goes into more detail about their working relationship but what struck me most was what he drew when she died. The Wall Drawing no. 46 was dedicated to her and was his first drawing using “not straight line”. He talked about how he watched her make Metronomic Irregularity and LeWitt had explained to curator Andrea Miller-Keller that ‘I wanted to do something at the time of her death that would be a bond between us, in our work. So I took something of hers and mine and they worked together well. You may say it was her influence on me.” (Roberts, 2012, p. 204-5). LeWitt and Hesse were entrenched in each other’s practice. This was little known, and LeWitt did not make this any public acknowledgment of her influence on him at the time. Metronomic Irregularity was dismantled after the 1967 show, and LeWitt remade the piece in 1993 for Converging Lines show at Blanton Museum of Art, in Texas. I think the impermanence of his own wall drawings, echo’s the ephemeral in Hesse’s Metronomic Irregularity, not existing until intricately and painstakingly installed. The interactions surrounding the making of Metronomic Irregularity II links it inextricably to Drawing number 46. Both pieces even though they no longer exist or with LeWitt’s piece sometimes it does exist they both hold a true sense of place. They are companions with wavering lines binding them through time, even if neither of them physically exists at the same time.

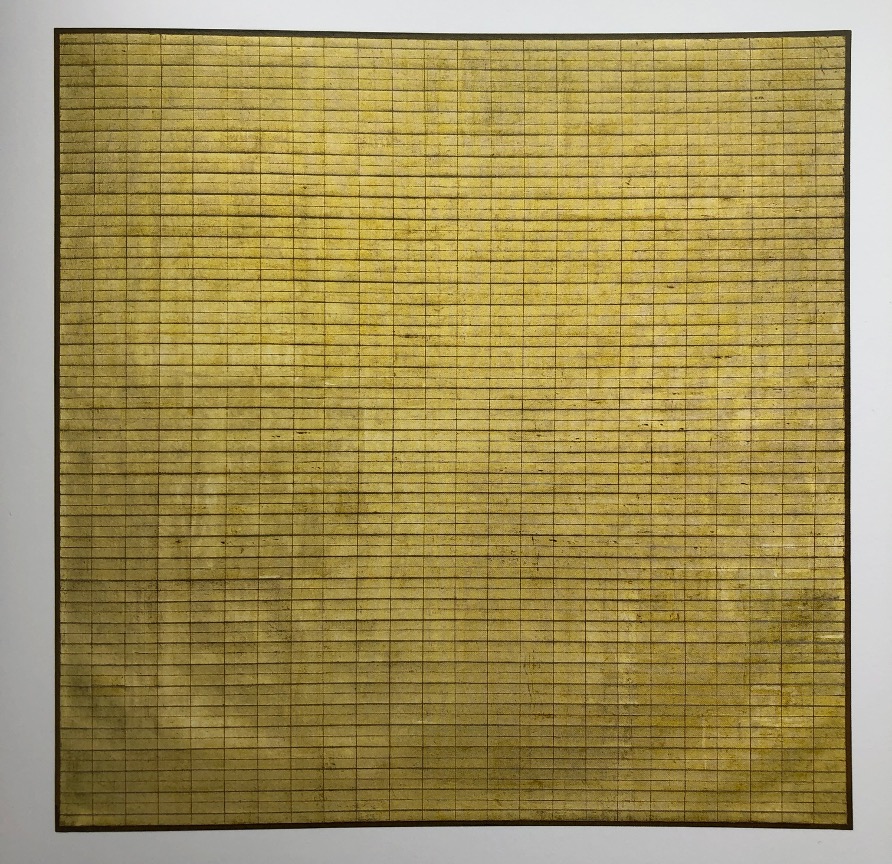

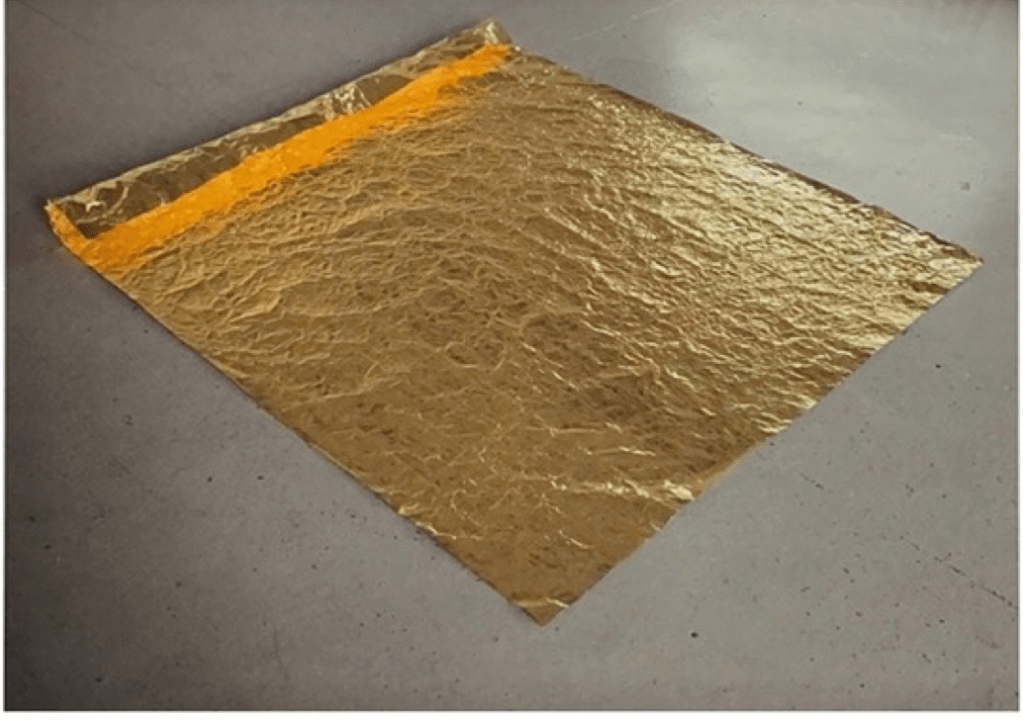

I looked also at the work of Agnes Martin. I know Morning (1965) fairly well as I have visited this piece at Tate Modern. It is the only Agnes Martin on public show in the UK and is therefore quite important for me to regularly visit. It is a piece that dissolves in front of you and when I am present looking at it, time seems to just stop. But in the research I wanted to find a piece that had meant her change of direction. This took me to finding out more about her transition period between 1958-1967 when she moved to New York and then left again. She made sculpture, paintings and drawings all around the grid. I had researched the Grid in my early practice and this features quite a bit in my own outcomes. I was really intrigued as to why she had made Friendship (1963), I wanted to find out what this meant to Martin and why the gold? I listened to Frances Morris talk about it on Great Women Artists podcast. I needed to find out more about this and her friendship with Lenore Tawney who it seemed may have given her the gold.

Two things occurred when Martin when made the painting she called Friendship. Firstly, she took a material object, the gold leaf and made it not into a two-dimensional painting, but somehow rendered it into a deeper space than the canvas afforded on its own. Secondly, she created a concrete yet glowing casting of a friendship with her close associate Lenore Tawney. Glenn Adamson writes that Martin created a ‘luminous gold painting called Friendship that could be interpreted as a tribute to Tawney, and also wrote her an extraordinary letter of thanks for an unspecified act of generosity’. (Adamson, 2019, p.73). Martin concluded this letter; ‘Any expression of gratitude is like the soundless sound. It is going to be like the waves over and over again. –Forever is not [sic] long. I think this is the “real thing”. Agnes.’ (Adamson, 2019, p. 73).

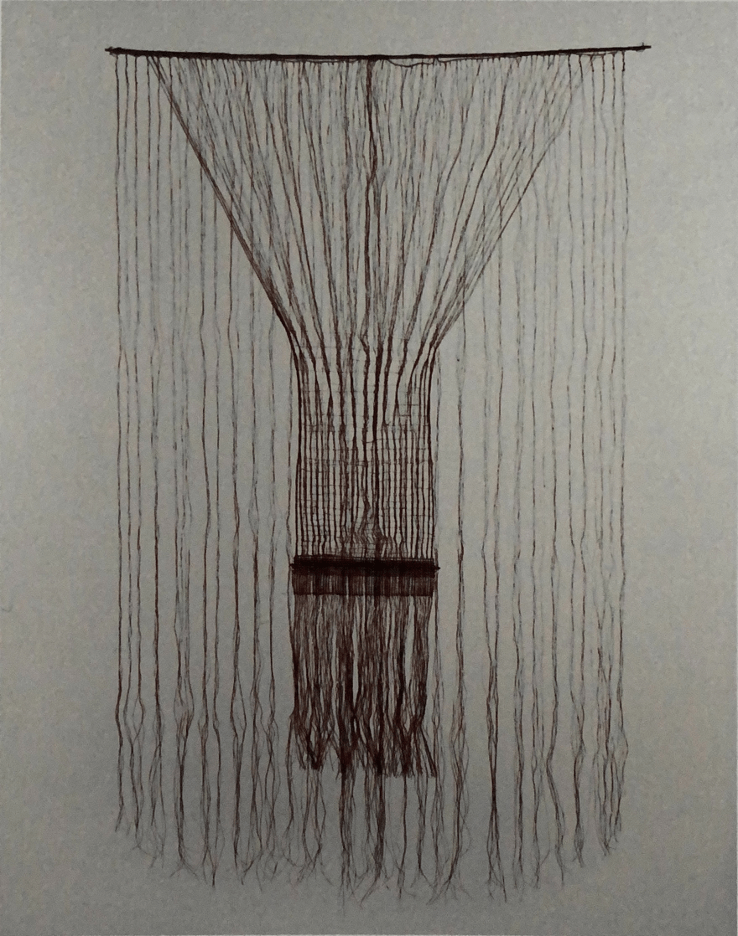

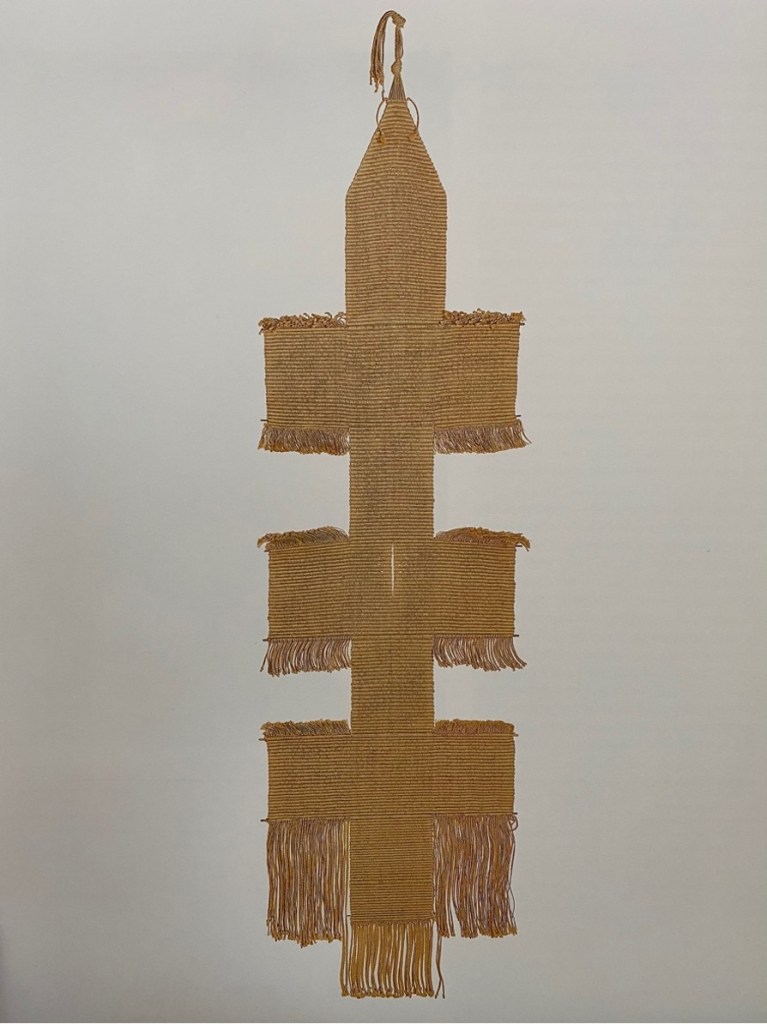

It is worth noting here, what Martin calls “real thing” is that her work was authentic, worth keeping a term she uses elsewhere in her writing. This unnamed gift or act changed Martin’s position and enabled her to ‘take my time and really get to work’ (Adamson, 2019, p.73). Olivia Laing talks about Martin wanting the viewer to be able to enter her paintings ‘like a parting a curtain. You go into it. I want to draw a certain response like this… that quality of response from people when they leave themselves behind.’ (Laing, 2021, p186). Laing concludes of Martin’s paintings‘All of her canvases stand ajar. Anyone can pass in. Anyone can experience white it feels like to let go of the things they carry, to be incorporated, just for a moment, into a world of love.’ (Laing, 2021, p186). This curtain image described by Laing, I cannot help but think again of Tawney’s work made in 1962, Lekythos, which stood fifty inches high curtain-like with a gridded centre, see Figure 6. This dialogue moving between works; White Flower, The Path, Friendship, Lekythos, the drawings they both made, and the collages by Tawney all lead to a companionship that led to the making of the piece, Friendship. I believe it was the beginning of this journey for Martin, both in its naming and in the circumstances; it was conceived, completed, and conveyed her onto a new path. Martin’s Friendship sits next to Tawney’s The Path, as a companion, it shows a friendship, which waned and was strained, but the two pieces born from it will endure linked as a pair, across time.

When I found the piece by Tawney, The Path (1962) I wrote to the Kathleen Mangan, the Executive Director of the Lenore G. Tawney Foundation because I just could not find any answers to the questions I had about this woven sculpture. Where had this piece been? It escaped any exposure online; I couldn’t find it in any third-party accounts of Tawney’s work. I could find no traces of it except for within the monograph of Lenore Tawney Mirror of the Universe only recently published by Mangan. Mangan replied, thanking me for asking such an interesting question. She confirmed that this particular gold leaf was atypical, Tawney had not used gold leaf in the other version of the Path series. In regard to how important this piece was to Tawney; she confirmed my suspicions that the piece had remained in Tawney’s possession. I quote here directly from Mangan’s reply. ‘The concept of the “path” was an important one for Tawney, representing her deep spiritual search and the journey we all take. In an undated journal entry, she wrote: “The Tao, a Path; the Way, The Absolute, the Law, Nature, Supreme Reason. Laotse says: ‘there is a thing which is all-containing, which was born before the existence of Heaven & Earth. How silent! How solitary! It stands alone & changes not. It revolves without danger to itself & is the mother of the universe. I do not know its name & so call it “The Path.'” (Punctuation and abbreviations are per LT.) (Mangan, 2021, p.1). The piece that Tawney had been so wild about, which had the inclusion of the precious gold leaf, never left her ownership and she only parted with it on the occasion of her death.

The idea Laing talked about in Everybody (2021) suggesting that Martin’s paintings were some kind of portal really was interesting for my own work. I have been working on drawings around portals and places to pass through, or that hold space physically or imagined.

Researching both Tawney’s work and Martin’s really gave me a sense that they were working in a psychological place when making their monumental works. This sense of place also holds in their drawings and workings which work on a much smaller scale. I also make drawings that are to do with the intimate and finding both their drawings using similar materials and qualities has really helped me find the permission to keep going with these parts of my practice.

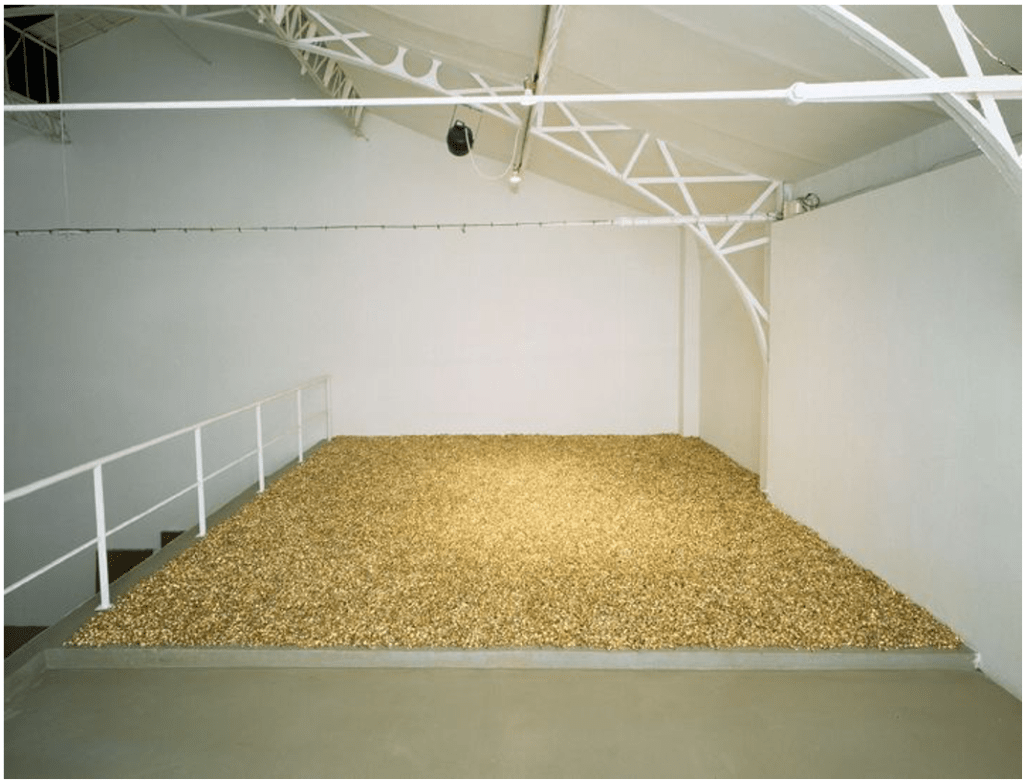

The final piece that I looked at in my dissertation was by Roni Horn(b.1955). My own interest in pairing objects had led me to research Horn’s work. I had found Gold Mats paired, for Ross and Felix, (1994-5) and the light that seemed to glow from the piece had the kind of presence that I hadn’t seen in any other work. When researching the work I discovered the story behind it and it fitted in so completely with my concept of companion works.

The Gold Field was finally shown in 1990 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, see Figure 15. Gonzalez-Torres and his partner Ross Laycock saw the piece. Gonzalez-Torres said it changed their lives. He described Gold Field as a ‘gift’ (Gonzalez-Torres, 1990, p.1). He wrote to Horn, stating: ‘The work was needed. This was an undiscovered ocean for us. It was impossible, yet it was real, we saw this landscape. Like no other landscape. We felt it. We travelled together to countless sunsets.’ (Gonzalez-Torres, 1990, p.3). He concluded, ‘we were given the chance to ponder on the opportunity to regain our breath, and breathe a romantic air only true lovers breathe.’ (Gonzalez-Torres, 1990, p.3). In 1993, after Laycock’s death from AIDS, Torres made Untitled (Placebo-Landscape-for Roni) as a response to Gold Field, Figure 16. Russell Ferguson described the installation thus: it ‘is itself a gold field, this one comprising thousands of candies, each wrapped in gold cellophane, Gonzalez-Torres had called Gold Field a gift; that was how he had received it, in a desperate time with Laycock already very ill. Placebo is literally a gift, actually thousands of gifts, since each viewer can take a piece of candy and make the work part of his or her own body by eating it.’ (Ferguson, 2009, p.113). This act of the endless edition is a disruption to the art market and a deliberate intention of the artist to make work egalitarian, available to all.

Unlike the previous artists I have discussed here, Horn and Gonzalez-Torres had no relationship prior to his viewing Horn’s work. He was a leading member of the collaboration Group Material a New York based collective who worked from 1979 to 1996. Gonzalez-Torres main collaborators in the group were Jenny Holzer, Julie Ault, Barbara Kruger, and Hans Haacke. Group Material were included in the 1985 Whitney Biennial. His Untitled – Placebo series, made a shift from gallery placement of value-based art to democratic ownership by making his work as endless editions and replaceable, in the displacement and picking up of the wrapped candy. The piece continues, for some installations, to unravel, deconstruct, as it is usual for the institution not to ‘tidy up’ for the duration of the installation, because by doing so would ‘intrude upon a ritual of transubstantiation.’ (Storr, 2016, p. 7.) In a recent interview with The Art Newspaper editor Ben Luke, Horn admits it was a great honour to be noticed and written to by Gonzalez-Torres (Luke, 2020). Horn and Torres began to talk and write to each and although Horn never met Laycock, she said in the same interview that Torres always triangulated the conversation as if Laycock were in it. Horn then made Gold Mats paired, for Ross and Felix in 1994-5, Figure 17. Gonzalez-Torres’s letter was published in 1994 as an essay. Horn had been asked by Gonzalez-Torres to read their letters out at his memorial. Horn described the consequence for her of being asked that, ‘we just shared a lot of the language, obviously expressed very differently, but the language was very, very close, organically close…. Thing’s kind of went back and forth. At some point, Felix was ill when I met him…., he called me one evening and wanted to talk about his memorial and asked me to speak at his memorial. It inspired the idea of the paired mats for the boys, and it was a shoe in for me because the pairing was already so big a part of my language, I loved that light in-between it was so perfect for Felix.’ (Luke, 2020). Luke summarises this interaction well when he states, ‘Yes there is a friendship, but it is a dialogue through art as well, which seems tremendously profound now and will live on long when we are all gone that dialogue is there in the form of art.’ (Luke, 2020).

This study was born from the idea of the artists making shifts in their works. Initially I noted that Martin moved from paint to gold. Lewitt moved from floor to wall, sculpture to wall drawing. Horn moved from mass to mat, glass to gold which because of its gauge was all surface. Then during the work, I noted that Tawney moved from smaller flat weaving to larger sculptural ceiling hung works. Hesse moved from wall to floor, wall hung objects to free standing sculpture. Gonzalez-Torres, in his work moved from placement to displacement, noting loss. In my own project I am looking at all of these dynamics and trying to find the language of my own to move my drawings into works in both two and three dimensions.

References

Adamson, G. (2019) Sculptor 1961 to 1970. In: Patterson, K. (ed.) (2019) Lenore Tawney Mirror of the Universe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Ferguson, G. (2009) Paired Gold Mats, for Ross and Felix. In: Horn, R. (2009) Roni Horn Aka Roni Horn. London: Tate Publishing.

Gonzalez-Torres, F. (1990) 1990: L.A., The Gold Field Essay. [Online] Available at: https://www.felixgonzalez-torresfoundation.org/attachment/en/5b844b306aa72cea5f8b4567/DownloadableItem/5ec823df5fc138f119efccb3 [Accessed: 29 January 2021]

Laing, O. (2021) Everybody A Book About Freedom. London: Picador.

Lippard, L. (1992) Eva Hesse. New York: De Capo Press.

Luke, B. (2020) A Brush With: Roni Horn. The Artists Newspaper Podcast. (2020) interview December 2020. [Online] Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4rChJ15Xfn4eLYZxEauXaF?si=kjRYkOlqR36s28BYRVQpzQ [Accessed: 16 December 2020]

Mangan, K. (2021) Question for Kathleen Mangan [E-mail]. Message to Culverhouse, T. 23 April 2021. Permission of Kathleen Mangan.

Roberts, V. (2012) “Like a musical score”: Variability and Multiplicity in Sol LeWitt’s 1970s Wall Master Drawings. [Online] Vol. 50 (Summer 2012). pp. 193-210. [Online] Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41703378 [Accessed: 10 January 2021]

Storr, R. (2016) When You See This Remember Me. In: Ault, J. (ed.) (2016) Felix Gonzalez-Torres. New York: Steidldangin Publishers.