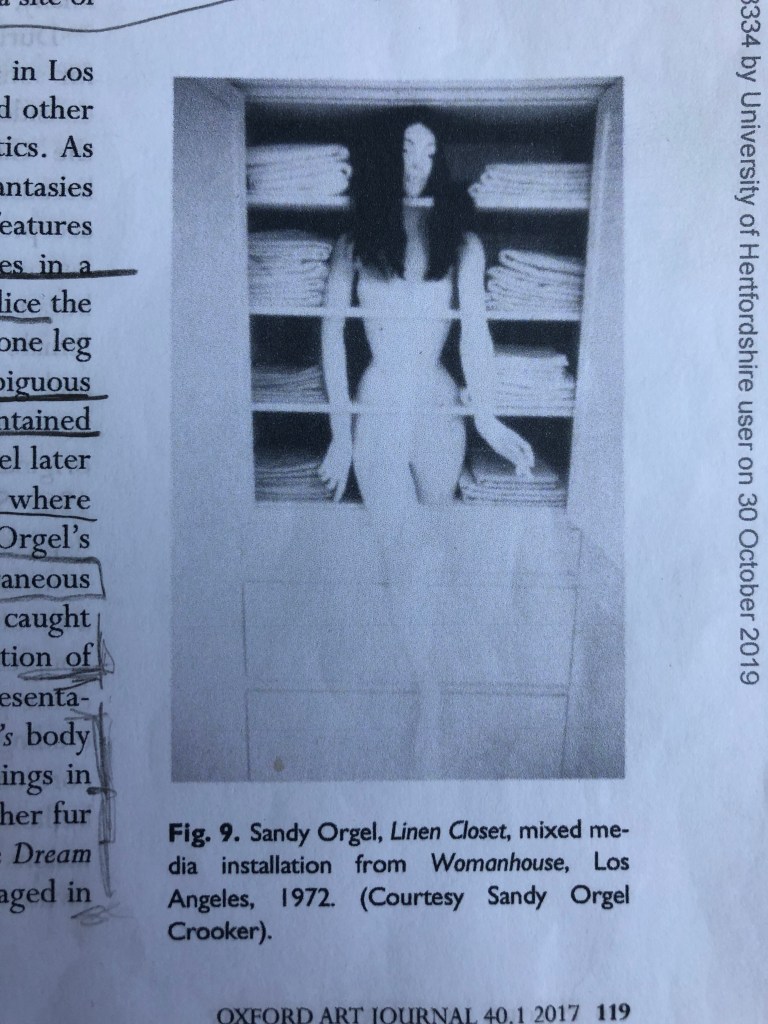

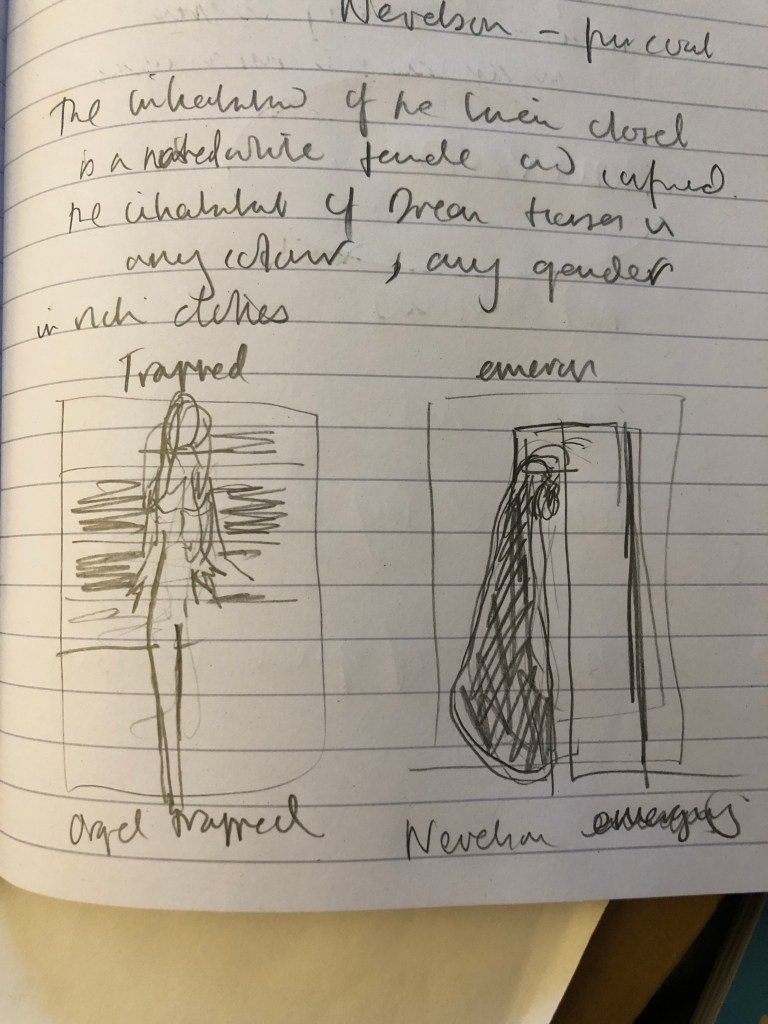

The excerpt I chose to study for the Critical Analysis in Research and Enquiry was complex. There was initial excitement at finding a piece of writing that expressed so many elements I am pursuing in my own practice. Taking the energy from that excitement, I had to get down to the nitty gritty of understanding the complex arguments within the text. It took many drafts trying to understand the various elements, but one element was being illusive so, I took to my pencil to try and really understand part of the argument the author was making about the differences in the two pieces of early feminist works by Louise Nevelson and Sandra Orgel respectively. Both were describing the plight of the feminist in the domestic, ritual and work driven female role. The evaluation of the pieces and how they contrasted were complex as she had drawn her conclusions by comparing two visual components within the article. One was of Orgel’s Linen Closet (Womanhouse, 1972), figure 1 and one was of Nevelson’s Dream House (1972) figure 2 from which she was performatively emerging (see below).

Fig 1 from Page 119 Oxford Art Journal 40.1 2017

Sandy Orgel, Linen Closet, mixed media installation from Womanhouse, Los Angeles, 1972

Fig 2 from Page 114 Oxford Art Journal 40.1 2017 Marvin W. Schwartz, Louise Nevelson with her sculpture, Spring Street Studio, 1972. Silver gelatine print. Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Special Collections. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Copyright Marvin W. Schwartz, 1972

The article in the wider context was claiming Nevelson for Bryan-Wilson’s queer theory. Nevelson had never been open about her relationship with her assistant and this is still not clear with her son denying this relationship. So for Bryan-Wilson to make the claims of Nevelson’s queer identity as an artist seemed a bit problematic. Bryan-Wilson states that she did ‘not need to know who slept in Nevelson’s bed in order to claim a queerness for her work or to understand that her art, unmoored from the distinctions between abstraction and figuration, or materiality versus metaphor, has provided queer artistic with a model of unconstrained opening. Furthermore, regardless of biographical ‘proof’, Nevelson has been taken up as a queer exemplar.’1 (Bryan-Wilson, 2017, p.121). Within my selected part of the article this isn’t explicitly mentioned but it is touched upon.

In her analogy Bryan-Wilson is saying that Orgel’s single white, naked and vulnerable female is trapped within the sheets and shelves of the linen cupboard whereas Nevelson herself is closeted but emerging, richly clothed, androgynous, ethnically in a minority by being an immigrant and definitely in a powerful position of control speaking on the telephone therefore disengaged from us, in a conversation we are not engaged with giving a nod to her liberty. This in context of the year it was taken could be the beginning of queer liberation, which Bryan-Wilson goes on to discuss further in the wider article.

So I drew out both of the images to try and understand them better. Making the visual argument through drawing helped me understand what Bryan-Wilson meant in her description of the dynamics of each piece by the counter-proposition they make. Orgel’s figure contained tightly within the domestic vision and Nevelson’s Dream House creating a space to dream of the infinite possibilities without boundaries.

I understood that Orgel’s work was indicating being about the egocentric self. But I was having trouble understanding how Nevelson’s work was the opposite. The author was also indicating that Nevelson’s life and identity was encapsulated in this photographic image of her emerging from her Dream House.

To find out more about the possibility that Bryan-Wilson was biased in her research and whether she was claims that could not be substantiated about Nevelson’s queer identity I started some deeper research on this and found an interesting online article on the Tate website about her work but this didn’t give me any answers about her queer identity. I found the book I had bought a book from the CAPC Museum of Contemporary Art in Bordeaux The Art of Feminism so checked out what it had to say about Nevelson. The authors (Gosling et al., 2019) had concluded the entire essay with a paragraph on Nevelson as an artist who pursued to change the domestic as a place for ‘new kinds of life and different kinds of relationships’2 (Gosling et al., 2019, p. 99). In the final line of the chapter they go on to state that Nevelson’s work ‘imagines the traditional home broken down and rearranged, able to hold what we might now call a queer feminist identity.’3 (Gosling et al., 2019, p. 99).

So I concluded from this further research that Bryan-Wilson isn’t the only art historian who is claiming that Nevelson’s identity as a queer woman was an important part of her feminist work and in breaking down barriers for women artists at this time by refusing to be politicised in her artwork or identity meant that actually it had more power and longevity.

Reflecting this research back to my own practice, I want the power of making to be more important than my own identity, like Nevelson, making this work in the area of a more allocentric (in the wider cultural context rather than just concentrating on my own lived experience, the term introduced to my by my personal tutor Kerry Andrews) approach in methodology. Making work that is relevant to all and other existence rather than just to myself.

1 Bryan-Wilson, J. (2017). ‘Keeping House with Louise Nevelson’, Oxford Art Journal. [Online]40 (1) pp. 109-131, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcx015 [Accessed 30th October 2019]

2 & 3 Gosling, L., Robinson, H., Tobin, A., Reckitt, H., Balshaw, M. and Arakistaina, X. (2019). The Art of Feminism. London: Tate Publishing.

Fig 1 from Page 119 Oxford Art Journal 40.1 2017

Sandy Orgel, Linen Closet, mixed media installation from Womanhouse, Los Angeles, 1972

Fig 2 from Page 114 Oxford Art Journal 40.1 2017 Marvin W. Schwartz, Louise Nevelson with her sculpture, Spring Street Studio, 1972. Silver gelatine print. Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Special Collections. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Copyright Marvin W. Schwartz, 1972